Playing Leapfrog

Start with an obscure state agency charged with developing clean energy, looking to make a name. Couple that with laws that create an artificial and insatiable demand for renewables. Now add a dollop of Wall Street money, eager for action. Before you know it, you have a volatile mix.

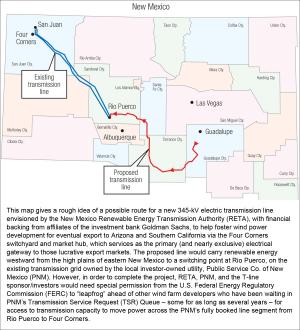

Welcome to New Mexico, where the state’s little-known Renewable Energy Transmission Authority (RETA) apparently has corralled a pool of dollars from Goldman Sachs earmarked for investment in a new electric transmission project known as Power Network New Mexico, LLC — 200-plus miles of 345-kV line to connect 1,500 MW of high-plains wind farms to the lucrative green energy markets of Southern California.

What better way to do business than to get the sovereign behind you in your bid to skirt the rules?

But there’s a problem. To deliver the power to its intended recipients, the project first must obtain delivery rights over the existing grid of local utility Public Service Company of New Mexico (PNM), which holds a hammerlock over access to the Four Corners switchyard. That’s the electrical intersection that acts as a chokepoint for any generator seeking to export power westward from the scrublands and high plains of West Texas and Eastern New Mexico, to the promised land of Southern California. Goldman Sachs and its financial partners want to complete their project by 2015, but can’t go forward without immediate assurance that such rights will be won. Yet no such guarantee is possible. That’s because, while the project would provide a wires link to allow wind farms in remote eastern New Mexico to deliver output to the larger grid, it can’t succeed unless it can garner transmission rights to carry the wind power across that last mile of congested line to the Four Corners gateway. For that, the project would need help from PNM, which owns the existing high-voltage lines leading from the Albuquerque-Santa Fe load center to the 4C hub. But the utility itself sees no motive to expand those lines – not for reliability (which isn’t threatened), nor to meet ratepayer needs (native load isn’t growing much).

So nothing changes. Meanwhile other would-be wind farm developers have been waiting five years or more to gain access into Four Corners for their own California exports, but to no avail. Yes, PNM might explore ideas to resolve the logjam in its congested transmission service request (TSR) project queue – as it did recently for its separate gen project queue. But the utility says that could take years, given the need for stakeholder engagement.

But money talks. And so RETA, PNM and Goldman Sachs, through its Power Network project arm, have proposed a unique and audacious solution. They asked the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) simply to set aside and waive PNM’s existing tariff rules for its TSR queue, and instead to let the project leapfrog everyone else and jump to the head of the line. In exchange for its commitment of millions to help foster wind power development in eastern New Mexico, Goldman Sachs would be assured of most-favored-nation status in gaining export rights to California. And in this power play, the project sponsors claim to represent the interests of New Mexico, as voiced through RETA, the state’s energy development arm.

What better way to do business than to get the sovereign behind you in your bid to skirt the rules?

Planning Made Simple

The sponsors claim in their waiver request that FERC has shown itself willing in a series of prior decisions to adjust project queues and allow some developers to leapfrog others – even in the face of protests from individual market participants with higher-priority queue positions that might be adversely affected by such adjustments – as long as the move will carry out key federal policy objectives. Such objectives include reducing queue backlogs, promoting new gen projects that are ready to proceed, and advancing progress in meeting state requirements under RPS laws that mandate renewable portfolio standards. (FERC Docket ER12-1699, filed May 2, 2012.)

Yet opponents question why FERC should favor one developer over another – even to the extent of setting aside tariff rules that govern who should go first – when the favored project hasn’t even passed muster through an open and fairly vetted regional transmission planning process. On one hand, RETA board Chairman Robert Busch testified in the case that his agency had commissioned the Los Alamos National Lab to study the problem of developing more renewable energy in New Mexico, which led to recommendations from LANL on various possible routes and corridors for new transmission lines. Busch said the LANL study had “validated the wisdom” of allowing the state legislature (through RETA) to focus on new transmission projects as the best way to foster green energy development in the state.

Yet, as Berrendo Wind Energy argues, the LANL study didn’t look specifically at the exact project now proposed, nor did RETA’s selection process include any transparent engineering or feasibility study, nor comport with the FERC’s established transmission planning principles. “Why does the unnamed project not seek to directly interconnect to Four Corners,” asked attorneys for Berrendo, “if it has the ability to finance and construct transmission at rates lower than the incumbent?”

Shovel Ready?

There was a time when PNM’s gen project queue – for studying the feasibility of interconnecting new energy and capacity resources to the grid – was just as clogged as its TSR queue, which allocates transmission line capacity delivery rights to gen projects that have won an interconnection agreement. The cause was well understood; with a first-come, first-served allocation system, developers would act quickly to lock in a preferential queue position, even if not ready to go forward.

Yet PNM reformed its gen queue a few years back. First, it divided the gen queue into two tracks: a “preliminary” track for more speculative projects, and a “definitive” track for projects ready to proceed. Second, it adopted a new priority rule: “first-ready, first served.” FERC approved the new scheme last year. (Docket ER11-3522, Sept. 30, 2011, 136 FERC ¶61,231.) Yet the TSR queue still suffers; its first-come, first-served scheme still favors developers who lock in their spot early, even if they then choose to sit.

The sponsors argue that FERC, by allowing their project to leapfrog earlier-queued requests for transmission rights, will help advance the admirable goal of favoring those projects that are shovel-ready. Yet some of those earlier-queued and higher-placed developers beg to differ. Consider Cargill Power Markets, LLC, a power marketer that holds the two top positions, 1 & 2, in PNM’s TSR queue, filed Feb. 21, 2008 (TSR No. 71946929), and October 24, 2008 (TSR No. 72608299). Cargill had sought transmission service from Blackwater node, in eastern New Mexico, to Four Corners. And Cargill argues that, contrary to claims made by the project sponsors, it never received an invitation to participate when the project sponsors conducted an informal open season solicitation process to gauge interest in the project among wind power developers.

As of early June, the sponsors were claiming Arrabella Wind LLC – an affiliate of Gestamp Asetym Solar North America – and First Wind Holdings LLC as possible anchor tenants to subscribe to the proposed transmission project. Arabella, which is believed to hold TSR queue positions 3, 4, 6, and 7, would thus leapfrog over Cargill if it signed on as an anchor tenant, and if the RETA project were to win a queue waiver from FERC. That the RETA project sponsors might have invited Arrabella to join, without asking Cargill as well, seems plausible, in light of the fact that the sponsors themselves said they intended eventually to conduct a second-phase solicitation of interest, “but with an emphasis on transmission service queue position.”

As Iberdrola Renewables, another opponent of leapfrogging, observed: “Offering to sell priority positions back to high-queued position holders once they have been superseded may be an effective business strategy … but presents significant harm to those same queue position holders.” RETA’s argument that FERC nevertheless should allow leapfrogging if it will mean bringing new projects on line fast also faces scrutiny.

The Lucky Corridor LLC, developer of a proposed 93-mile, $350 million, merchant transmission project slated for northern New Mexico (http://www.luckycorridor.com/), and which also has attracted support from RETA, questions whether the Goldman Sachs project is really shovel-ready. “It is unclear,” according to attorneys for Lucky, “whether Power Network or its customers are commercially viable and ready to proceed... For example, there is no representation that Power Network has demonstrated the functional equivalent of site control, nor has any representation been made that the possible customers of Power Network [such as Arrabella or First Wind] have demonstrated site control for their proposed generating projects.”

State-Sponsored Equity

The Tres Amigas Project, which has proposed to build a unique, three-pronged super-cooled and super-conducting DC power ring at Clovis, New Mexico to allow large transfers of renewable power between ERCOT and the Eastern and Western Interconnections, has also weighed in, raising questions about the proper role of state agencies in merchant project development. As it happens, Clovis isn’t far from either the proposed start point for the RETA project, or the location of Cargill’s top-queued transmission service requests, and so Tres Amigas is quite familiar with RETA’s initiatives in New Mexico. But Tres Amigas questions whether a quasi-public agency such as RETA, established by the state legislature to foster renewable energy development, should be allowed to become an active equity player: “RETA was one of the reasons Tres Amigas chose to locate its project in New Mexico” … [but] “RETA has changed its focus to becoming a transmission owner … using its eminent domain rights to compete with private investment... In this regard, RETA contends that it is not a market participant and has no market bias, but Tres Amigas understands that RETA will have an equity stake in the proposed merchant project.”

This new prospect – of state agencies dabbling in merchant energy – certainly bears watching. And in that respect, New Mexico isn’t unique. Across the Rocky Mountain West, at least a half-dozen other states have gone this same route, creating quasi-public state agencies to foster renewable energy development and infrastructure, including:

· Wyoming Infrastructure Authority (http://wyia.org/)

· Kansas Electric Transmission Authority (http://www.kansas.gov/keta/), and

· South Dakota Energy Infrastructure Authority (http://www.sdeia.com/).

The testimony can leave the impression that as a state agency created by statute, RETA was feeling heat to prove its worth. Thus, when it discovered that Goldman Sachs was ready to move, with dollars in hand, the momentum was irresistible, regardless of the technical merits or feasibility of the project. As RETA’s Executive Director Jeremy Turner testified in the case: “It was not until RETA sought out and found … infrastructure investment funds managed by direct or indirect subsidiaries of The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., that the project got underway in earnest.”

When big money put on the table, it’s hard to resist, even if it means stepping on toes. As RETA chairman Busch testified in the case, in perhaps ironic fashion: “Time is of the essence and legal delay is the weapon of choice for those who seek to game the system.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Bruce W. Radford is Fortnightly's publisher.