Capitalizing on Consolidation

The number of shareholder-owned electric utilities has declined by 48 percent since 1995. Over the next decade, we expect to see two or three deals per year, on average. At this rate, the number of U.S. investor-owned electric utilities would be reduced to less than 40 by the year 2020. Although the pace of consolidation remains moderate relative to other industries, it is a significant disruption to the utility industry. Indeed, some utilities are likely to move forward into the M&A fast lane in the next three to five years, opening up the potential for the largest utilities to grow even bigger.

A number of factors and forces are easing the path to consolidation in the industry.

Untapped Value

Variations in operational performance across the utility industry indicate significant improvement potential—what we identify as “untapped value.” For instance, some companies are spending three or four times as much as others per customer for critical functions such as customer care. While elements of this discrepancy can be explained by regional differences, regulatory requirements, and similar factors, the majority of the performance gap is due to inefficiencies in the industry and to regulatory constructs which do not incentivize utilities to drive operational and cost improvements. Industry-wide, there is approximately $4 billion annual operations and maintenance (O&M) untapped value, which is roughly 10 percent of the annual O&M spending for the industry. As we can see in Figure 1, there is significant variance of performance in each of the three major O&M categories—transmission and distribution O&M per customer, customer care O&M per customer, and administration and general O&M per customer. In all cases, there is a long tail of performance in the fourth quartile.

Performance Indicators by Quartile - Utility O&M Costs per Customer

Performance Indicators by Quartile - Utility O&M Costs per CustomerIn the context of this untapped value, there is considerable potential for higher-performing companies (i.e., first and second quartile performers) to acquire lower-performing companies (i.e., third and fourth quartile performers) and yield operational benefits for their customers and shareholders.

Macroeconomic Uncertainty

Recent economic recessions have played a significant part in merger activities over the last two years. For instance, more than 75 percent of the mergers involved acquirers with lower three-year revenue growth buying companies with higher three-year revenue growth. Many utilities have seen customer load significantly decline—a greater than 20 percent reduction over a five-year period for a few utilities.

In addition to the more recent financial crisis, future uncertainties could drive those with higher economic risks to consolidate as a means to diversify their portfolio. Depressed interest rates are softening the pressures from these economic uncertainties, but the historic lows will not last forever. M&A has been—and will continue to be—used to diversify a utility’s exposure to an economic region and customer base, to increase the contribution from regulated earnings, and reduce wholesale exposure through a natural retail hedge. These factors have driven many mergers in the last few years and will continue to do so in a low-growth, more uncertain environment.

ROE and Capex

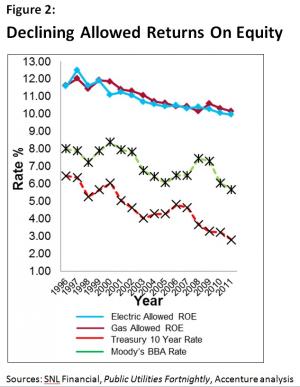

Declining Allowed Returns on Equity

Declining Allowed Returns on EquityIn the past 15 years, there has been a steady decline in allowed return on equity (Figure 2). While to a certain extent this measure of profitability is intrinsically linked to variable interest rates, the decline will continue to put pressure on utilities to cut costs. Utilities are faced with fewer levers to drive sustainable 5 percent to 7 percent earnings growth—especially given limited/non-existent, non-regulated revenue growth opportunities. Consolidation provides a mechanism to reset financials and drives earnings growth through economies of scale.

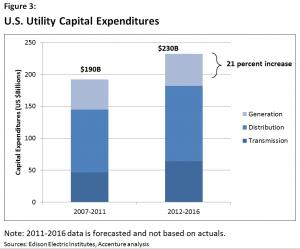

At the same time, capital investment is projected to grow significantly over the next five years—driven mainly by transmission capacity enhancements and distribution replacement, reliability improvements, and smart grid and advanced metering infrastructure (AMI) efforts. Access to capital is essential to support these investment opportunities; those companies that have higher capital costs or weaker balance sheets are at a significant disadvantage. When compared to utilities in other industrialized countries, the fragmented nature of the U.S. utility industry places the country at a disadvantage; further consolidation would help to carry out the grid modernization efforts necessary to fuel the nation’s growth.

Personal Motivations

As in all industries, the personal motivations of a small number of key decision makers are often the greatest driver behind consolidation. Two forces make up the personal factors that can drive consolidation:

· An increase of 71 percent in change of control compensation provision for CEOs in the last 10 years increases the personal motivation to sell their companies—particularly when those same CEOs are approaching retirement age; and

· An ever-present group of leaders—as in other industries—that have personal ambitions to become or remain the leaders of the largest U.S. utilities.

U.S. Utility Capital Expenditures

U.S. Utility Capital ExpendituresUnfavorable Headwinds

The path towards consolidation is not without its challenges, which might keep the industry rate of consolidation slower than other industry sectors such as telecommunications or financial services. A number of factors can continue to create an unfavorable headwind and moderate the pace of consolidation:

· The fragmented federal and state regulatory model;

· Increasing federal scrutiny of deals;

· Often onerous gain-sharing of merger benefits with consumers, which act as a disincentive;

· Somewhat ill-defined regulatory hurdles—as was the case in a recent merger where the state regulator changed its M&A standard from “no net harm” to “substantial net benefit” when evaluating merger activities;

· Rising utility equity valuations—evidenced by higher price-to-earnings ratios—rising by about 33 percent in the last three years—which might tend to moderate a willingness to pursue acquisitions. Utility stocks, with their steady dividend payouts, are enjoying higher overall prices. Although all-stock deals might not be affected, utilities companies must determine if the best return on investment is a whole company transaction, as opposed to an asset deal—which is often a more risky acquisition of wholesale generation, attempting to pick the bottom of the market.

The Pace of Consolidation

Further evidence that the pace of M&A will continue is found in the regulatory approvals of mergers in the last two years, reassuring the industry that the approval process—while still lengthy—can reach favorable rulings from both state and federal regulators.

While there is no indication of a rush to mass convergence in the near future, we believe the pace of consolidation will remain steady and sustained due to a variety of factors. As our analysis has shown, a recent merger of two utilities companies was driven by the promise of untapped value (beyond the usual merger synergies), macroeconomic uncertainty (specifically de-risking the competitive portfolio), higher capital investment requirements, and personal motivations. Indeed, companies that move beyond the more obvious benefits—such as balance sheet improvements, reduced hedging costs, and corporate back-office consolidation—to tackle more fundamental integration can drive a step change in operational improvement. Companies with strong operational discipline, defined processes, scalable operating models, standardized technology platforms and low-cost structures will be well positioned to drive shareholder value through the scale and reverse value destruction historically associated with M&A activity. Utilities need to decide whether their future is rooted in inorganic growth and refocus their strategy, or if they intend to proactively position themselves to take pole position in the race to consolidate.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS: Jack Azagury (jack.azagury@accenture.com) is an executive director at Accenture and the North American management consulting lead for the Resources industry. He is located in New York. Ted Walker (ted.h.walker@accenture.com) is a senior manager in Accenture’s Utilities industry strategy group. He is located in Washington, D.C.